This interview was conducted at Haneda airport, Tokyo, when Toshiki Okada was returning from Munich Kammerspiele, the national theater of Germany, two days after he had opened a new piece called NŌ THEATER which he had written and directed. Okada makes several distraught statements such as “Japan is slowly committing suicide” and “we are at war with ourselves.” What does he mean by them? And what are his reasons for remounting his play Five Days in March this year -- which marks the 20th anniversary of the founding of his company chelfitsch?

Interview : Hiroyuki Yamaguchi / Photo : Naoki Takehisa

Awaiting the return of Toshiki Okada from Munich at Haneda Airport

Hiroyuki Yamaguchi(interviewer) :

Welcome home.

Toshiki Okada :

Thank you for meeting me here.

You must be tired from your long journey.

I’m not too bad. Although I can’t say I’m full of energy either.

It sounds like you’re feeling normal.So you’ve opened the new repertory piece for the Munich Kammerspiele?

Yes, we opened and I was happy with it, and now I’m home.

You were happy with audience reactions? Or with yourself?

I meant that I was able to create something I was satisfied with. I’m relieved because I was able to have the audience come and see it for the first time, and being among them, I got the sense that everything I wanted to communicate was received by the audience. So that’s satisfying, not just in terms of this project in Germany, but in general.

Now, this year marks the 20th anniversary of the founding of chelfitsch. Do you have any particular thoughts or feelings about that?

To be honest, I don’t. Which may just be because it’s not as if I’ve been working with the same company members for the last 20 years or anything.

Did you have any particular thoughts on the 10th anniversary?

Not really. Back when I first founded the company, we weren’t as active to the extent that we are today. But coincidentally it was our 10th year when we had our first overseas performance. And that was a major turning point.

Does 20 years seem long to you?

I feel surprised at having made it this long.

I guess you’re not the type who finds temporal markers significant.

You’re probably right. I started doing theater when I was in college. I was 19 years old. There are plenty of people who start doing theater in middle school or high school. And I thought that compared to them, I was behind and couldn’t really say that I’d been at it for a long time, but when I hit 38 and realized I’d been doing theater for more than half my life, it was a shock.

How would you divide the life of your company chelfitsch in terms of different time periods?

I’d say the first period was the first three years that we were doing it as an extension of our college club. After that group dissolved, I applied to be part of ST Spot and got a slot in their showcase festival – that marked the beginning of our relationship with ST – so from that point up to the production of Five Days in March in 2004, I would consider the second period. Five Days in March broadened our activities on many levels; it brought us outside our sphere. That piece marks the beginning of our third period.

-

(from March 16、2006 issue of “MONO Magazine”)

-

(The End of Toil 2005)

Would you say that the Great East Japan earthquake in 2011 marked the next shift?

My way of thinking changed drastically then, and the style of my plays changed with it. But that was really something that happened to me on a personal level; I don’t see it as a turning point for chelfitsch.

Then in terms of chelfitsch, the company’s still in the midst of a long third period?

I don’t know what I’d point at to mark the fourth period yet.

Based on noh methodology: a story of slaughter reinterpreted as greed, and a story about feminism through the eyes of women who cannot fulfill their deepest desires

You just created a new play in Germany called NŌ THEATER; can you tell me what kind of piece it is? I’ve only heard that it has something to do with noh, ghosts and greed.

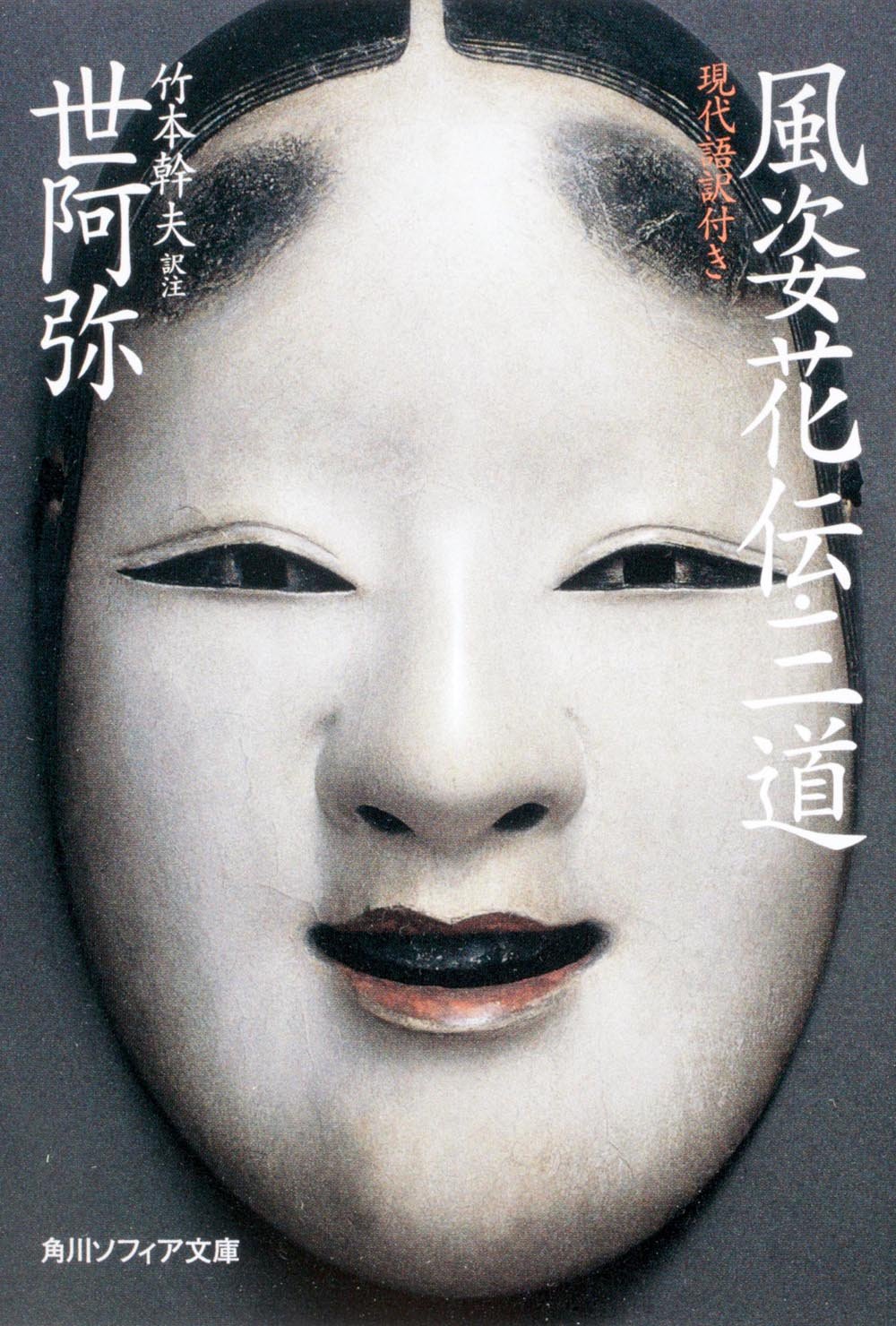

There’s a book by Ze’Ami called Three Paths. To put it simply, it’s a how-to book on how to write a noh play. If you read this book, you can make a noh play. So I started to make a new play following the stories and narratives in noh and sticking to the format of how to incorporate music. Of course the stage set, costumes and music are completely different from what’s used originally in the noh theater, but I still think what I made is a noh play.

So you created something that follows the methodology of noh theater, structurally.

The crucial thing to me in the story format of noh is that the protagonist is a ghost of an discontented spirit. This format happens to lend itself to very political stories. When I thought about whether there are any modern-day people who have died with discontented spirits, of course they are all over the place. In most cases, the reasons these people have discontented spirits lie in social issues. In other words, to portray such characters naturally leads to a socially conscious, political story. I was most interested in this point. Rather than the fact that noh is a traditional Japanese art form, I was struck by how practical the formula that Ze’Ami developed is.

It’s also important that noh is a form of theater that is performed with live music. The performance takes place on stage with equal weight on the musicians and the actors. I think that this is really fascinating.

-

(c) Julian Baumann

-

(c) Julian Baumann

NŌ THEATER contains two noh plays. The first is a story about greed. The shite (main actor) is a man who had worked as a trader at an investment bank. The other play is about feminism, and the shite is a woman. Each of the plays refers to an original noh song. The greed play, whose theme is slaughter, is based on plays in which a hunter is the protagonist. In other words, I’m pulling directly from the story concept of someone who is punished for his sins and suffers greatly. I wondered what could correlate to such a deep sin as killing in contemporary terms, and I thought of unbounded greed for wealth. For the story about feminism, I looked to original noh plays in which a woman is unable to fulfill her deepest desires. Stories about women warriors, or Lady Shizuka. I was inspired by those plays.

-

(c) Julian Baumann

The theme of greed seems connected to your previous works in which you address labor issues, shifts in power, or currency collapse – but feminism seems like a completely new topic. How did you settle on those two themes?

In my mind, I have an image that Japanese society is slowly committing suicide. We should be doing something to prevent our demise, but we can’t. The concept behind this production is to express this image from two lenses -- that of economics and politics -- and to present these two views in one package.

Would it be accurate to interpret your image of “society slowly committing suicide” as that of Japan after the earthquake?

Yes, that’s how I see it. Without question, the earthquake was the catalyst for me to think about society in that way.

Matthias Lilienthal, the artistic director of the Munich Kammerspiele, said in an interview that the new piece also touches on late capitalism. He must be referring to the play about greed?

I think so.

When you’re making a play for a theater abroad, are you swayed by outside influences in terms of your choice of theme?

Well, for example, my interactions with Mattias affected me greatly. He’s very good at prodding artists and activating them. When I’m talking to him, I get a sense that he has used all kinds of way of stimulating other artists up to now.

The production you made was for the theater’s repertory, and after writing and rehearsing the play, you won’t see it after the premiere. Any future productions of it would be completely in the hands of the theater. As a director, how do you handle that? Because you won’t be able to refine the production through watching performances.

Performances naturally improve over time before audiences. Even if the director is not there. If you look at their website you can see that the selection of performances are different everyday – that’s the way theaters in Germany function; that’s what it means to have a repertory. They strike and load in huge sets every single day. I got used to that system too, and have stopped thinking about it as particularly strange.

And as a side note, I’m not sure why this is, but apparently in Germany sometimes there are directors who don’t even come to opening night. I even had an actor ask me “Are you watching the show on opening night?” I was going to watch, of course. But for them apparently it’s not an obvious answer.

Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and a Farewell Speech performed by German actors

I saw a photograph from a production of Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and a Farewell Speech you created as a repertory piece. In the picture, an actor was doing a backbend on a table. It was quite a departure from the original production as we know it.

-

-

(from the German production of Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and a Farewell Speech (C) Julian Baumann)

-

-

(from the Japanese production of Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and a Farewell Speech (C) Dieter Hartwig)

That’s right, we did go in that direction.

That play was characterized by a physicality that was described as “slackening.” I was surprised that it changed that drastically in the hands of German theater actors.

I’m sure I don’t need to say this but what’s important is reality. The question is, whose reality? One of them is of course my reality as the director. But theater is not something that’s created by one person, so the realities of those involved in the production become part of the process, of course, and the production is enriched by that. Even if I had asked the actors at Kammerspiele to perform that “slackening” physicality that seems to be considered the defining style of chelfitsch, I’m sure it would not have resulted in anything interesting. The reason is that when I made that piece with chelfitsch with Japanese actors, there was already a shared reality between myself and those actors, and in fact I took that reality for granted when I created the play. But in Germany, I have no such shared reality with the actors I’m working with. That’s not anything discouraging to me. Because it’s a chance to discover something new. Instead of an assumption of a shared reality, we have to approach each other through conversation and tackle aesthetic questions and questions of craft. In the productions of NŌ THEATER and Hot Pepper, German theater actors are playing Japanese people – in the theater, this isn’t a strange occurrence at all, because that’s how theater is, right?

The reason for remounting Five Days in March with actors who are 24 years old and younger

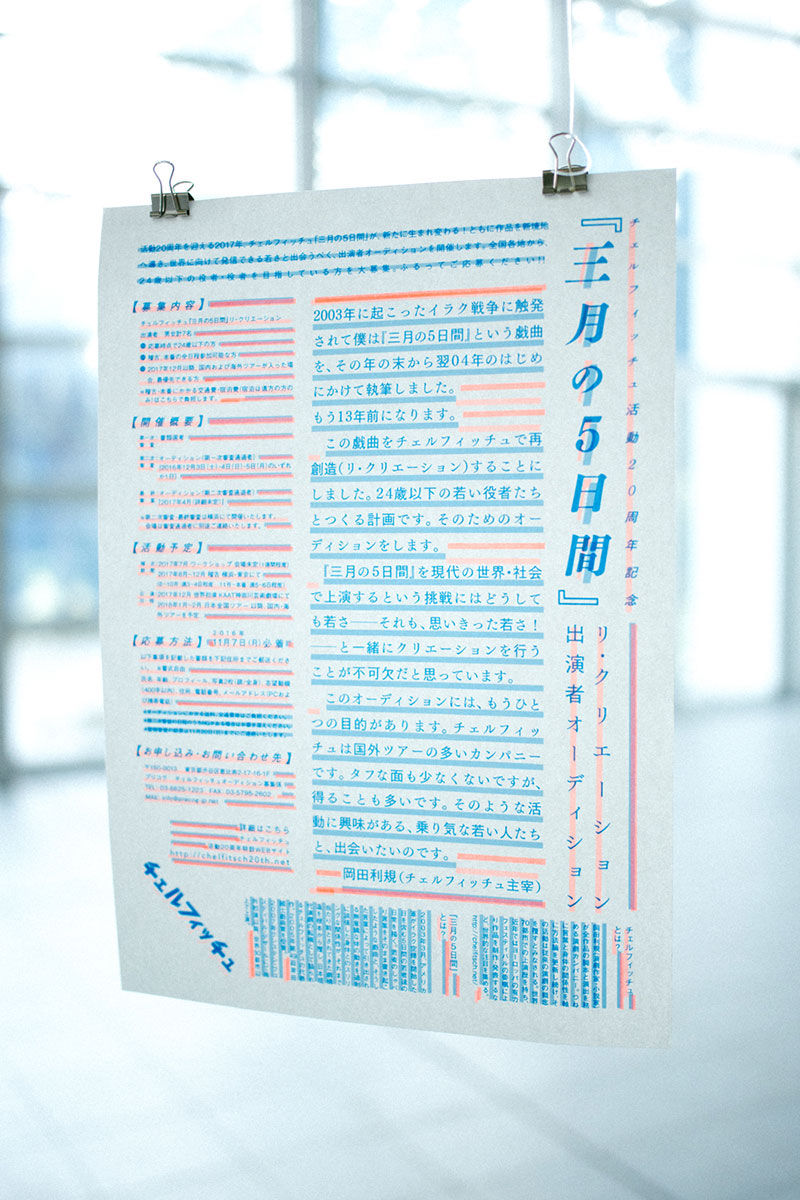

This year, you’re remounting Five Days in March. Similar to the way you had completely new actors in your play in Germany, you’re not casting any original cast members but instead you’ll be working with a completely new group of young actors under the age of 25.

For me, the things I’m looking for in actors has changed pretty drastically from before, and it’s connected to everything I’ve experienced up to this point. To be specific, in this third period of the company when we were increasingly performing abroad, certain issues came up. I started not only presenting work I’d already made in festivals overseas, but creating new work in the context of international collaboration. The way we raised money for these projects changed, the places I went to create work changed, and my thought process also changed. My perspective and my objectives were also influenced by these factors and changed. For me, all of these changes were positive. But they weren’t necessarily so for all of the participating members of the productions. For example, since I am a director, I can still work abroad through a translator. But that’s not the case for actors. They have to speak text onstage; it’s not easy to imagine working as an actor outside Japan. On top of that, for an actor to be on tour for two or three months at a time means that during that time s/he has to turn down job offers in Japan. That is just one example. There was an unevenness in our motivation towards work overseas. Perhaps I could have shared a larger philosophy or something about it within my company, but I didn’t. This was the issue that came up during the third period.

And now, I’m auditioning young people for the remount. I want to meet people before they become professionals in the Japanese theater scene. I’m hoping to expose people to our working style first. At the audition interview, I asked them “What is your ambition in life?” People whose answers were in the realm of “I really love theater and…” were not chosen to advance in the audition process. Only people who possessed something larger than that remained. There were actually many more strong young people than I’d anticipated, so it seems extremely promising. Not just in terms of finding great actors for this production, but in terms of our future entrusted to the next generation.

So will the actors selected for this production continue to be involved in future chelfitsch activities?

Of course that possibility exists. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be so. My intention is not merely that it would be fun to remount Five Days in March with a bunch of young, interesting actors. I want ambitious young people to be exposed to my creative process and experience touring, and contribute their thoughts. I think that will be a meaningful experience for them. Whatever they do after that is up to them, whether they continue working with chelfitsch, or whether they even continue with acting or not. That’s why ambition is crucial.

So your aim is not necessarily to nurture the talent pool of the larger theater scene.

That wouldn’t be a fitting framework for someone like me who’s cutting people who say, “I really love theater” from the audition process. (Laughter.)

That’s true. (Laughter.) The word ‘ambition’ came up earlier – what kind of new ideas do you expect from the next generation that could not have been possible from actors up to now?

I want theater to have as profound an effect as possible on society. My hope is that the sense of society expands so that through performance, something new is born that serves to connect to new ideas. I want the next generation to lead that way. Demanding people who are motivated purely out of their love of theater to be more socially conscious doesn’t seem sensible -- in fact it seems outright a nuisance. But I personally hope that the young people who enter the field are people who grasp theater with a larger perspective, with a socially conscious frame.

Were there people with no theater experience at all at the auditions?

There were. There were some people who came to the auditions because they’re drawn to socially conscious work.

Those auditioning for this project probably never experienced the Iraq war with a sense of reality as it is portrayed in Five Days in March, simply because of generational differences. Is your hope that they will connect that event with their social consciousness through understanding your script?

There was someone who auditioned, for example, who was six years old at the time of the war on Iraq. Even the oldest actors permitted to audition, at the age of 24, were in grade school 13 years ago. Those who were in middle school back then are not eligible to audition. On the one hand there were some people who have vague childhood memories of the war breaking out, and that in itself feels fresh. But I don’t necessarily need actors to connect the Iraq war portrayed in Five Days in March with their own lives. I just want them to have ambition, or interest, or curiosity towards the war and beyond.

Don’t categorize things into country, region, or peoples. The focus is on the individual.

You returned from Munich today and your next project is taking Super Premium Soft Double Vanilla Rich (premiered 2014) to Thailand, and then a collaboration project with Thai artists. How do you prepare for productions in various places, including Japan?

I don’t know how to answer questions like “What is it like to work in Europe and be heading into your next project in Asia?” What I can say is that I think I don’t work with the framework that those questions assume. For example, on this trip there will be a collaboration with Thai artists. But I don’t put the focus on “collaboration with Thais.” Nor am I putting focus on “production in Asia.” What’s most important to me is who the collaborating artists are. This time I happen to be working with artists who are Thai, who live in Thai society and portray Thai society in their work -- so their expressions may particularly reflect a Thai or Asian way. As for working in Germany, I have continuously been given the opportunity to create new work by an artistic director named Mattias Lilienthal. I support his vision, and I’m happy to be a part of it. That’s why I do it. That’s all, basically. I can say the same for noh theater. It’s not that I have some particular feelings about traditional Japanese art forms and all that, but I happen to be fascinated by a form created by an individual named Ze’Ami.

So what’s important to you is not what country or region you’re going to be working in, but with whom – and what that person is thinking about. Ultimately there might be projects you have to take on in any case, but you can apply this thought process no matter where you are working, right? Did you always approach projects in this way?

No, only as a result of a certain amount of experience.

By the way, I’ve heard that these days, you’ve been using not only politics and economics as key words for your work, but also history.

Did I say that? (Laughter.) History connects us to the imagination, which is very important in the theater, as well as what I happen to be very interested right now: ghosts. Without imagination, you cannot bring history to life before you. In other words, you can only perceive the present moment as you see it in front of you. It’s the same with ghosts. Ghosts are a genius invention that allows us to bring the past to life in the present – they are history itself. Imagination is a necessary strength. Without it, we cannot see history overlapping with the present, we cannot see ghosts. In other words, we could not enjoy the power of the invention called ghosts, and more than that, without imagination, we could not experience the theater.

We are at war with ourselves. Does the future hold despair? Where is hope?

You said that Japan is in the midst of committing suicide. In another interview, you pessimistically said that after the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, there would be no work for you in Japan. Can you see any possibility for a bright future?

To be honest, I don’t. I can only see division and civil war in the present situation. And for someone like me who is engaged in acts of expression amid this situation, it poses the huge problem of what I’m supposed to do. In other words, should I work towards the end of fracture and war? Or engage in the war? Honestly I don’t know what to do. However, I can’t believe that ending the civil war is the solution. I just couldn’t say that, casually. That would be the same as saying that what I believe is just, and everybody ought to believe me. If we truly value our beliefs, and we believe that the present condition is not acceptable, then we have no other choice but to engage in civil war. I’ve even stopped thinking that it’d be better for us to mend our divisions to be whole. But I also don’t think that the thoughts I just described are admirable. I really don’t know what to do.

Your question about a possibility for a bright future – the subject of that question would be considered “Japan.” For me, there are times when I don’t want to think of “Japan” as the subject – that in fact it’s not necessary. Because I don’t think there’s a bright possibility for her. The future is grim. But that doesn’t mean that my future, or your future, as an individual, is necessarily grim. It’s entirely possible for your future to be bright – that is entirely up to you. Of course, that’s an easy thing to say. In the mean time, the power of a nation is pervasive, and practically speaking, we have to pay taxes and utilize government services and infrastructure. Otherwise the garbage trucks will stop picking up our trash. So in that sense, the country and its individuals are in the same boat. But still, we can think about country and individuals separately. There are people who are capable of doing so. On the other hand, there are those who don’t think that way. And our civil war is taking place between those two kinds of people.

That reminds me, I saw several plays while I was living in Munich. One of them was a production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. When I read The Cherry Orchard after the earthquake, I thought the story was about Fukushima. Because it’s about people having to leave their home. But when I saw it recently, it felt to me like a story about the arrival of the Trump era. The system of values we believed in without question has suddenly been undermined. How do you react to that? That’s what the story was to me. This is the super basic power of theater, or indeed, fiction.

*The repertory system is standard practice in the public theaters in Germany, in which selections of productions of classical plays and new plays are performed by the actors in residence at the theater on different schedules daily.

Toshiki Okada

Born in Yokohama in 1973. Playwright / Director / Novelist. He formed the theater company chelfitsch in 1997. Since then he has written and directed all of the company's productions, practicing a distinctive methodology for creating plays, and has come to be known for his use of hyper-colloquial Japanese and unique choreography. In 2005, his play “Five Days in March” won the prestigious 49th Kishida Kunio Drama Award. He participated in Toyota Choreography Award 2005 with “Air Conditioner (Cooler)” (2005), garnering much attention. His collection of short stories titled "The End of the Special Time We Were Allowed" was published in February 2007 and awarded the Oe Kenzaburo Prize. He has been on the judging panel for the Kishida Kunio Drama Award since 2012. In 2013, his first book on theatrology was published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha. He has widened the sphere of his activity to art exhibitions as well. He displayed a video installation titled "Four Unremarkable Things You See at Train Stations" at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo in 2014, handled curation duties for some of the exhibition space for a special exhibit at the same museum in 2015, and produced new works for the 2016 Saitama Triennale. Meanwhile, he is engaged in the creation of works by the new technique of "video theater." He was in charge of the script and direction for "Wakatta-san no Kukki" in the children's program at the Kanagawa Arts Theater in the early part of 2015. In the same year, he staged "God Bless Baseball," his first play based on Japanese-Korean collaboration, as the opening program at the Asian Culture Center, the biggest cultural complex in all of Asia, in Gwangju, Republic of Korea. In 2016, he prepared and staged "in a silent way" as a performance project jointly with dancer and choreographer Mirai Moriyama under the curation of Yuko Hasegawa at the Setouchi Triennale. In the same year, he began a commission to direct works in a repertory program at the Munich Kammerspiele, one of foremost public theaters in Germany, for three consecutive seasons.

http://chelfitsch.net