"EIZO-Theater Manifesto"

Toshiki Okada

Wouldn't it be interesting if we stopped confining use of the word "theater" to a mode of expression?

Let us instead use it to refer to the mode of thought applied when creating "theater" as a mode of expression.

What is created through the use of theater as a mode of thought will be theater, whether or not it is "theater."

What is theater? Theater is a fiction as phenomenon engendered by performance at a certain place.

What is fiction, then? Fiction is an alternative reality.

Theater therefore engenders an alternative reality at a real place. In other words, it is nothing less than the generation of this alternative reality as a phenomenon.

Insofar as it is a phenomenon, fiction as phenomenon may be likened to a rainbow. If we could say that the rainbow phenomenon appears in the minds and hearts of the people viewing it, we could also say that the phenomenon that is theater arises in the minds and hearts of the audience. The rainbow hangs in the sky and, by analogy, theater arises at the place where it is performed. This characterization sits far better with me than the aforementioned one.

If this is not "theater" as a mode of expression and can be apprehended as something whose performance in a certain place engenders fiction as phenomenon, then the use of theater as a mode of thought will presumably enable us to think about it and intervene in it.

In short, we should be able to apprehend what is not "theater" as theater, create it as theater, and make theater that is not "theater."

Now wouldn't that be interesting?

As an attempt to make theater that is not "theater," I have begun working on EIZO-Theater.

It is precisely in EIZO-Theater that part of the latent power of theater which cannot be actualized in "theater" will presumably be endowed with a clear form.

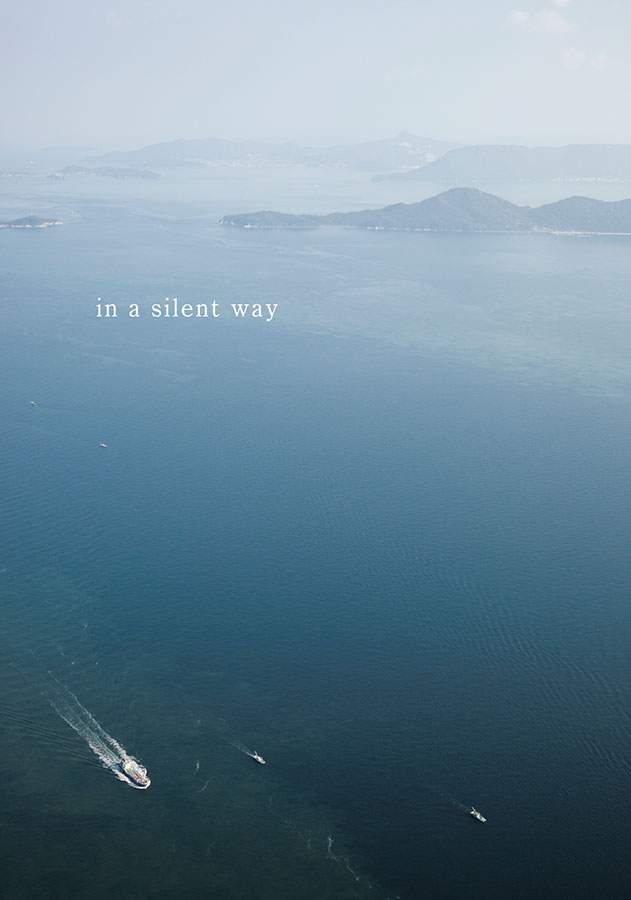

EIZO-Theater attempts to present works utilizing image projection as a theatrical performance. I and Shimpei Yamada, a stage video designer who has embarked on this approach with me, gave it the name "EIZO-Theater."

In the production of EIZO-Theater, we use theater as a mode of thought and the projection of images as the technique. This is to say that EIZO-Theater rests on images as theater and their projection as theatrical performance.

The space where an EIZO-Theater work is displayed is also that where EIZO-Theater is performed.

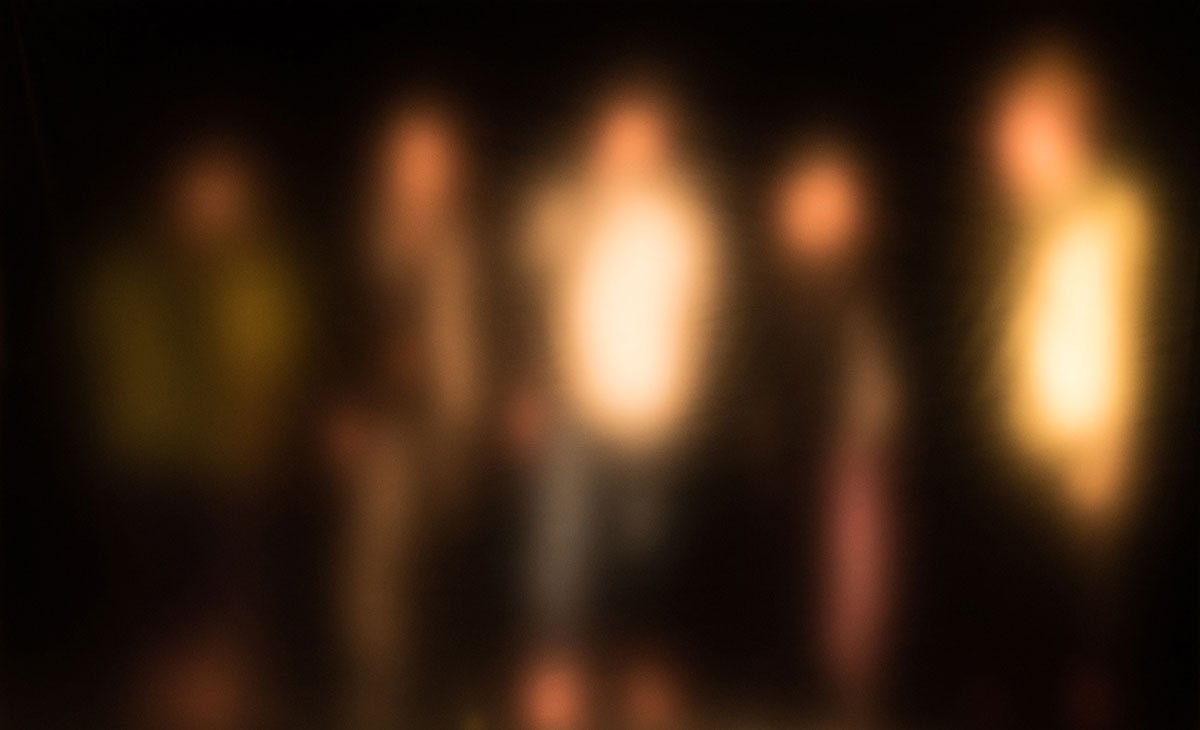

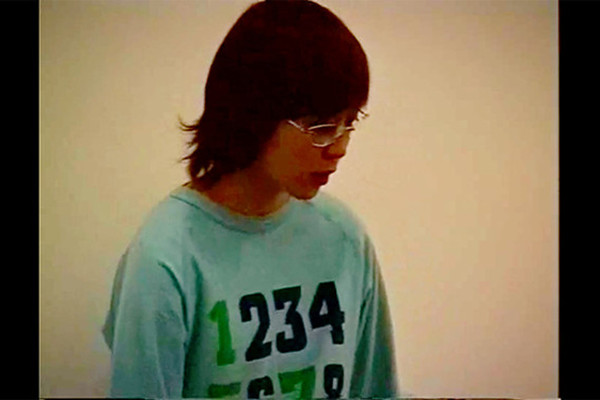

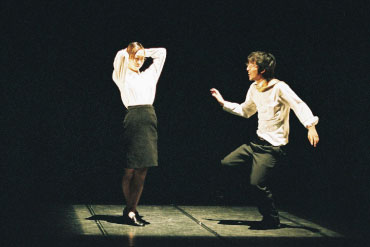

The images projected in EIZO-Theater are taken with a fixed camera shooting the whole bodies of actors who act on the basis of the script containing their lines.

EIZO-Theater does not use images of only a part of the body. For example, it does not apply the technique often used in films of showing close-ups of faces.

EIZO-Theater does not use any techniques that change the framing, such as camera panning, shooting on a dolly, and zooming in or out.

The images used in EIZO-Theater do not have backgrounds. They are photographed with pure black or pure white backgrounds made using background paper.

The bodies of the actors acting in the images used in EIZO-Theater are projected in actual size (i.e., the same size as their real bodies).

The actors' bodies in the images used in EIZO-Theater may make their entrance or exit by moving in or out of the frame, but do not appear or disappear by being cut in or out.

The above may be considered general rules formulated to support the fiction that human bodies exist where the projections are seen. Through this methodology, EIZO-Theater imitates "theater."

Because they are only general rules, however, there are also exceptions. For example, in one EIZO-Theater piece, the whole body of an actor is displayed on the screen of a smartphone left on a table, and consequently is not actual-sized.

In EIZO-Theater, members of the audience can scrutinize the movements and condition of an actor's body in even more detail than they could while watching conventional "theater."

In EIZO-Theater, members of the audience can move up close to the projected image of an actor's body to get a better look at it. In "theater," they are normally not given the option of this sort of appreciation. This is possible with EIZO-Theater exactly because, in form, it is similar to a display or exhibition as well as a performance.

In EIZO-Theater, members of the audience can inspect the bodies of the actors without any qualms and more closely than they could while watching real bodies in "theater." This is because the bodies are nothing more than projected images.

Yet even bodies that are only image projections are imbued with presence. This is why the EIZO-Theater audience members in practice cannot scrutinize the actors' bodies as images entirely without compunction. The presence imbuing these images is powerful enough to make those who attempt to take a close look without reserve feel hesitant or guilty about doing so. This effect is very intriguing. The presence of the images may be regarded as resembling that which actual human beings have. It can also be said to have a distinctive reality of its own, of a sort that we do not feel from actual people, or at least do not sense as keenly. There is something ineffable about it. The presence of bodies in EIZO-Theater is perhaps close to that of a ghost.

In theater, the bodies acting and the speech issuing from them engender fiction as phenomenon. This also applies (mutatis mutandis) to EIZO-Theater.

But in EIZO-Theater, the actors engendering fiction as phenomenon are those who are not actually on the site of performance and whose images are projected there. The presence of the actors on the site is nothing more than a fiction.

In short, two fictions overlap in EIZO-Theater. One is the fiction as phenomenon engendered at the place of performance by the actors. It is the fiction on which the theater rests.

The other is the fiction that the actors are actually present. It is the fiction resting on the technique of image projection.

In EIZO-Theater, one fiction presents another fiction as phenomenon.

The induction of a fiction resting on image projection, i.e., the fiction that actors are really present on the site of performance, is not in itself sufficient to be termed "EIZO-Theater." Unless it is also engendering the fiction engendered by bodies acting and speech issuing from them, i.e., the fiction resting on theater, it is not EIZO-Theater.

The product of the projection of images from photography of acting bodies in cinema and that in EIZO-Theater differ completely from each other. EIZO-Theater is not a type of cinema.

The fiction induced by acting bodies and the speech issuing from them in EIZO-Theater must be a fiction of the sort that operates on the site where the images are projected - the space where EIZO-Theater is exhibited/performed. If it is not of this sort, it will not be EIZO-Theater, however much the fiction composed of those images is depicted by the cinematic technique.

When deciding on "EIZO-Theater" as the name for this attempt, we took a hint from the word "grapefruit."

The word "grapefruit" is simply a combination of the words for grape and fruit. Properly speaking, it should mean grape, but it means something completely different instead.

Furthermore, as everyone knows, although grapes are a type of fruit, grapes and grapefruit are two different things. This character was a kind of aspiration of ours.

The appellation "EIZO-Theater" quietly reflects our ambition to create a theatrical equivalent of grapefruit.

First publication: "EIZO-Theater Manifesto," Toshiki Okada, in "Shincho," June 2018 issue, pp. 167 - 171.

Partially revised for republication in a catalog.

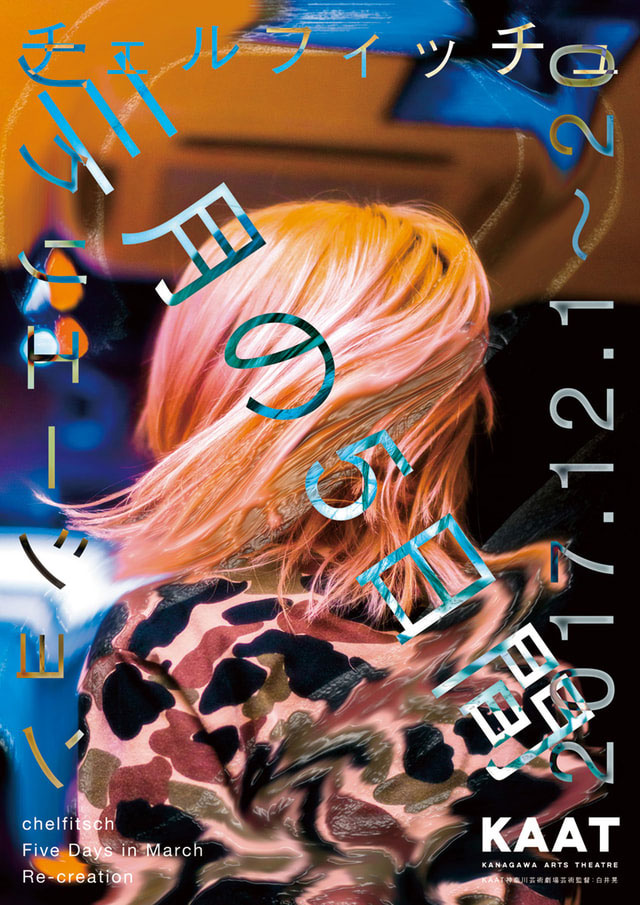

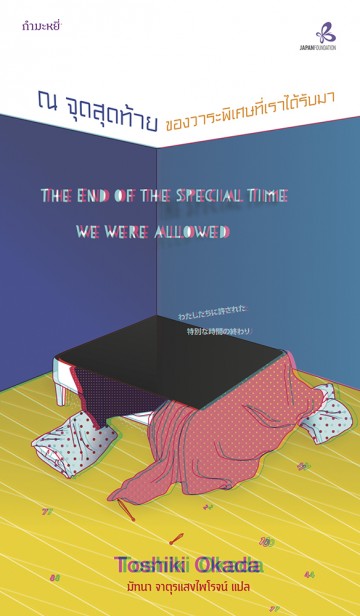

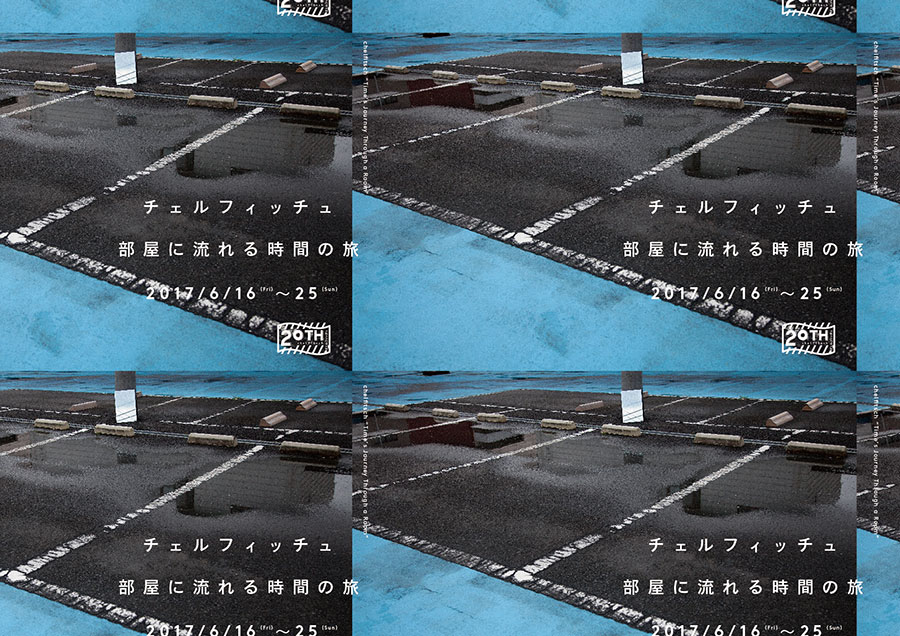

![『三月の5日間[リクリエイテッド版]』](https://chelfitsch20th.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/324493.jpg)

coming soon